The men who directed the Enola Gay over the city were ready for anything that day and at the same time unprepared.

The pilot of the aircraft, Paul Tibbets, had cyanide capsules in his pocket in case the crew members were captured, but they continued their mission undisturbed until they could drop the device on the target; no one knew that the detonation alone would cause a number of victims between 65 and 70 thousand and they did not even expect to see such an intense light.

Although the official statements of the soldiers are of general indifference, it seems that some of them wrote down in their personal diaries phrases of repentance made famous by many films.

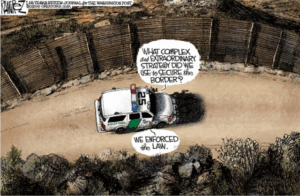

Jack Webb, TV series

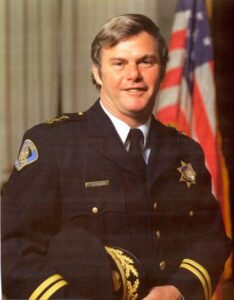

Chief Joe McNamara

AND FOR THE HECK IF IT:

A history of… Easter eggs

This weekend many people around the world will be variously painting, hunting for and eating (chocolate) eggs (quite possibly all three). My local supermarket has shelf after shelf of Easter eggs on display at the moment, but why do we eat them and when did this all begin?

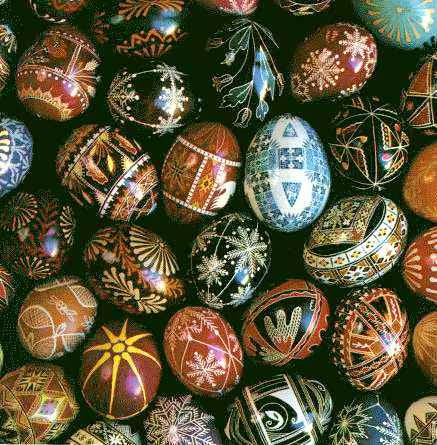

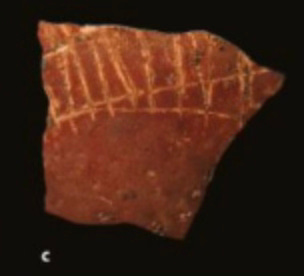

Humans have been decorating eggs for a long time. A very long time. 60,000 years ago the Kalahari Bushmen were using ostrich eggs as water bottles. They would drill a hole in the end of the egg, empty the contents and fill it with water and plug the end with grass or beeswax. They would hold around a litre (two pints) of water and were surprisingly robust. They would also often be decorated, the surface being carved or painted – possibly to indicate ownership or perhaps because they simply wanted them to look nice or convey a symbolic meaning.

In Ancient Egypt it was traditional to celebrate the ‘Season of the Low Water’ (also known as the ‘Season of the Harvest’) in what is now mid-May. It was, unsurprisingly, the point at which the water in the Nile was at its lowest prior to the beginning of the its annual floods. The word for ‘Low Water’, šmw, transliterates to Shemu, a festival first celebrated perhaps as long as 4,700 years ago and which continues to this day with the name ‘Sham Ennessim’. Painted eggs were and are very much a part of this celebration, as Molefi Asante observes:

On that day … the modern Egyptians say that lettuce represents hopefulness at the beginning of the spring. Eggs are used to represent the renewal of life in the season of the spring. People dye the eggs in various colors in a tradition that goes back to the ancient Egyptians who were probably the first to introduce this practice.

Eggs were an obvious symbol of the start of spring, and as such were of course in abundance at the time but they had another, greater significance. Many cultures have within their mythos the concept of the ‘cosmic egg’ (alternatively ‘world egg’ or ‘mundane egg’) – an object that is present at the beginning of time and ‘hatches’ to create the universe (or a being who then does the same). Often the shell and white of the egg becomes heaven in these stories and the yolk becomes the earth. In ancient Greek mythology this ‘Orphic Egg’ was described in these terms:

From the egg, everything came forth, the heaven and the earth, the sea and the stars, and all the gods and goddesses

For more than 2,500 years decorated eggs have been an important part of Zoroastrian tradition in the celebration of the new year at the start of spring in a festival now known as نوروز, (‘Nowruz’ or ‘New Day’) celebrated by people of many faiths across modern-day Iran and Central Asia. Just before midnight of the day before Nowruz, celebrants gather around a Haft-sin table usually adorned with painted eggs that represent the cycle of life and the struggle between order and chaos.

Decorated eggs were clearly a significant part of spring celebrations across many pre-Christian cultures, but how did they become associated with the resurrection of Christ? The word ‘Easter’ is thought to derive from ‘Ēostre’ or ‘Eostrae’, a goddess associated with spring and fertility in Anglo-Saxon paganism. We have clear evidence to support this in the writings of the Venerable Bede (672–735):

Eosturmonath has a name which is now translated ‘Paschal month’, and which was once called after a goddess of theirs named Ēostre, in whose honour feasts were celebrated in that month. Now they designate that Paschal season by her name, calling the joys of the new rite by the time-honoured name of the old observance.

The only problem is that this is the only reference we have to Ēostre, though inscriptions have been found that mention matronae Austriahenae believed to be the same, or a similar deity. As for the name name Ēostre, it is linguistically linked to the Old High German Ostara and is thought to derive from the Proto-Germanic austrōn, meaning ‘dawn’, which in turn comes from the Proto-Indo-European root aus-, meaning ‘to shine’. This root is also the source of the modern English word ‘east’, indicating the direction of the sunrise.

Christian celebration didn’t, however, simply take both its name and its egg obsession, from a pre-existing festival. There is a legend, most commonly found in the Eastern Orthodox Christian tradition, that after the death of Jesus, Mary Magdalene went to the Emperor Tiberius to protest against the cruelty of Pontius Pilate during Christ’s trial. Upon meeting she offered the emperor an egg and said “Christ is risen!” to which Tiberius retorted words to the effect that it was about as likely that Christ has been resurrected as it was that the egg in her hand suddenly turned red. You can probably guess what happened next! (Another version of this story has the egg in her hand turning red when she discovered Christ’s tomb was empty.) The colour red is considered to be of particular significance, representing the blood that Christ shed on the cross.

Whether or not this actually happened, this story is most likely the start of the tradition of dyeing eggs red at Easter which continues to this day in Greek (and other) churches.

The formal adoption of the egg as a symbol of resurrection by the Catholic Church came in 1610 with the publication of the Roman Ritual which includes in the Easter Blessings of Food:

Lord, let the grace of your blessing + come upon these eggs, that they be healthful food for your faithful who eat them in thanksgiving for the resurrection of our Lord Jesus Christ, who lives and reigns with you forever and ever.

This served to ratify a long-existing practice, as we know from the royal expense roll of King Edward the First of England from 1290:

18 pence for 450 eggs to be boiled and dyed or covered with gold leaf and distributed to the royal household at Easter.

(I know that the price of eggs is a topical issue in the USA at the moment. This equates to around nine days’ salary for a labourer, so they earned the equivalent of 50 eggs a day. That works out to about $2.50 per egg in today’s terms, so despite the recent price rises they are still cheaper than they were 750 years ago! I am not sure if this price includes the boiling, painting and gold leaf, though).

One reason for the continued association of eggs with Easter is that they were frequently forsaken during the preceding Lenten fast, and as a result surfeits of them would accrue. Writing in The Frauds of Romish Monks and Priests in 1725 Gabriel d’Emiliane reported:

The Italians do not only abstain from. Flesh during Lent, but also from Eggs, Cheese, Butter, and all white Meats. As soon as the Eggs are Blest, every one carries his portion home, and causeth a large Table to be set in the best Room they have in the House, which they cover with their best Linnen, all bestrew’d with Flowers; and place round about it a dozen Dishes of Meat, and the great Charger of Eggs in the midst. ’Tis a very pleasant sight to see these Tables set forth in the Houses of Great Persons, where they expose on Side-board Tables (round about the Chamber) all the Plate they have in the House, and whatsoever else they have that is rich and curious, in honour to their Easter Eggs, which of themselves yield a very fair shew; for the Shells of them are all painted with divers Colours and gilt. Some. times there are no less than twenty Dozen in the same Charger, neatly laid together in form of a Pyramid. The Table continues in the same posture cover’d all the Easter Week, and all that come to visit them within that time, are invited to eat an Easter Egg with them, which they must not refuse.

When did people go from simply eating eggs to hiding (and thence hunting for them) as well? Some claim that Martin Luther (1483–1546) came up with the idea in the 16th century, encouraging men hide eggs in their gardens for their wives and children to find. We definitely know, from the writings in 1682 of the German physician and botanist Georg Franck von Franckenau (1643-1704), that there was a folk belief of er Oster-Hase (Easter hare) that laid Hasen-Eier (hare’s-eggs) which were hidden in gardens and the nearby countryside for children to hunt for. Over time the hares turned into rabbits and so we have the Easter bunnies of today.

What was originally a Germanic tradition spread across the rest of Europe, and we find the young Queen (then Princess) Victoria writing in a letter in 1833, “Mamma did some pretty painted and ornamented eggs and we looked for them.” She then continued this tradition for her own children, writing in 1843 that Prince Albert:

…hid some coloured Easter eggs in the moss for the children… It is not so many years ago that I used so to enjoy hunting for and finding Easter eggs.

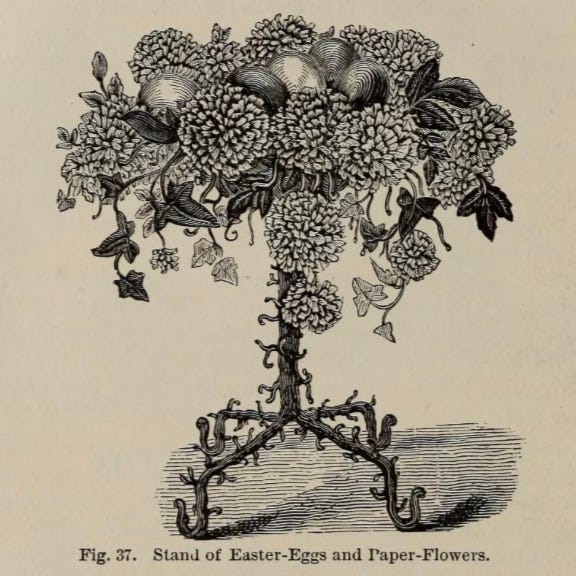

These eggs could be painted hen’s eggs, but also by this time artificial eggs, made of papier-mâché, had also started to become popular in wealthier households. These would be elaborately decorated and hollow, usually filled with sweets or gifts. Such was their loveliness that they would be retained as keepsakes and put on display at subsequent Easters.

When most people think about Easter eggs today they, obviously, think of chocolate eggs. It is widely claimed that the first chocolate eggs were consumed at the court of Versailles by King Louis XIV of France (1638–1715) but I have struggled to find a decent source for this. I have similarly not been able to substantiate the assertion that:

In 1725, in Torino, the widow Giambone, who owned a small shop on Via Roma, started creating the first chocolate eggs. She had the idea of filling the empty eggshells with melted chocolate: the idea had much success among the Turinese people.

What we can be certain of is that in 1873 the British chocolate company J. S. Fry & Sons (better known as Fry’s) made the first hollow chocolate eggs by pouring paste into moulds. Two years later, in 1875, rival Cadbury created a smooth cocoa butter that enabled the production of what we would think of today as a modern Easter egg (they went on to merge with Fry’s in 1919).

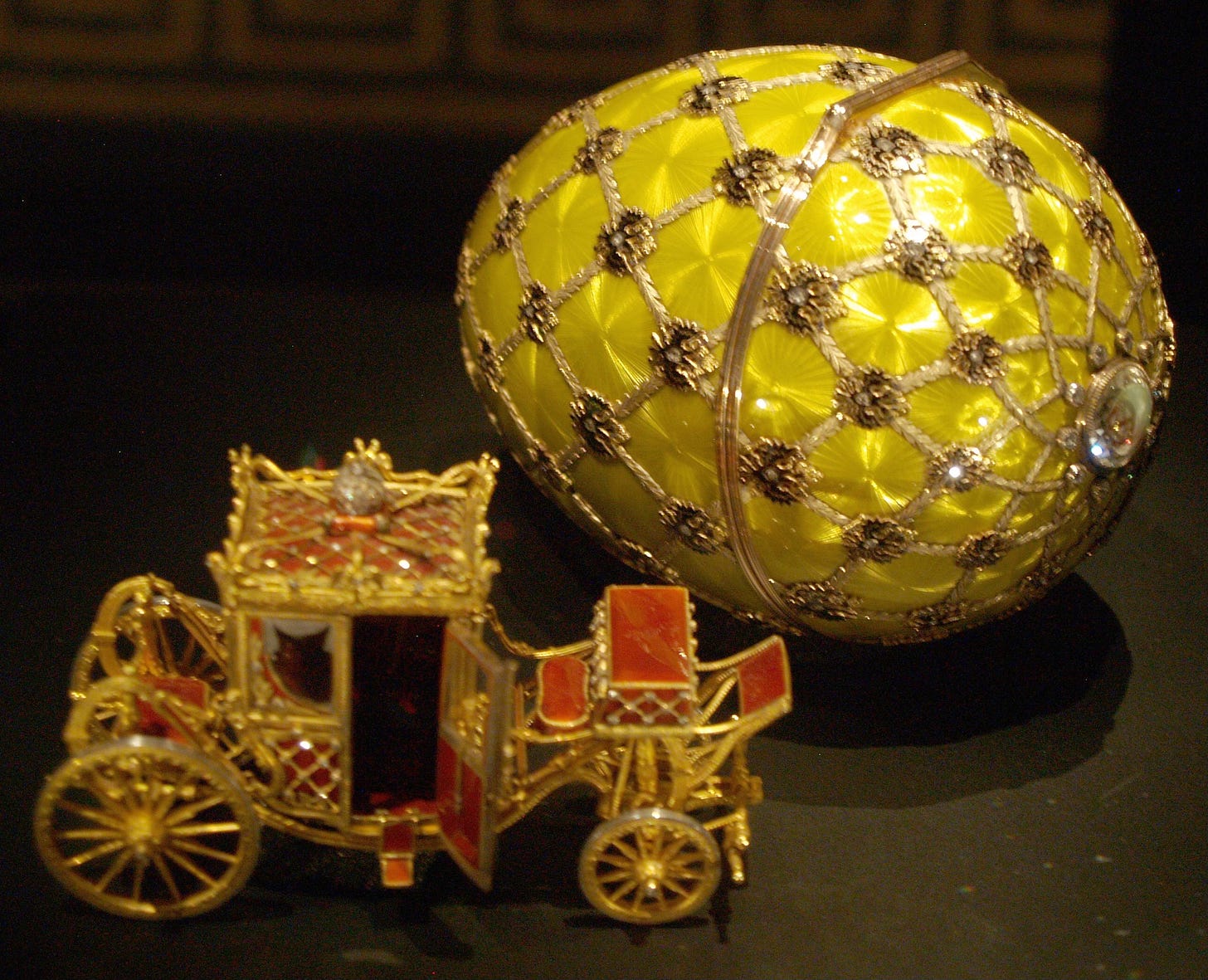

Properly the most famous, and definitely the most expensive, Easter eggs of all time were the ones made by Peter Carl Fabergé (1846–1920), 50 of which were made for the Russian royal family between 1885 and 1917, of which 44 have at least partially survived. The first egg, known as the ‘Hen Egg’, was probably based upon one made for the Danish royal family in the 18th century. At around 7cm (2.5 inches) long it had a plain, enamelled exterior with a simple gold band but opened to reveal a tiny golden hen sitting on golden straw, and inside the hen was a tiny diamond replica of the imperial crown. The Empress Maria Feodorovna was so thrilled with the egg that Fabergé was given free rein to create the future eggs however he saw fit. Each egg was a beautiful object in itself, and each contained an astonishing ‘surprise’. Probably the epitome of his craft was the Imperial Coronation egg, made in 1897. Its surprise was a 10cm (4-inch) replicate of the 18th-century Russian imperial coach recreated in exacting detail – a gold body, platinum tyres, rock crystal windows and working shock absorbers. It is very hard to put a value on it today, but is almost certainly worth more than $20,000,000. I think it fair to say that the Easter eggs I consume this weekend will be somewhat cheaper!

what???speak up

|

STATE OF THE UNION

|

C’ya

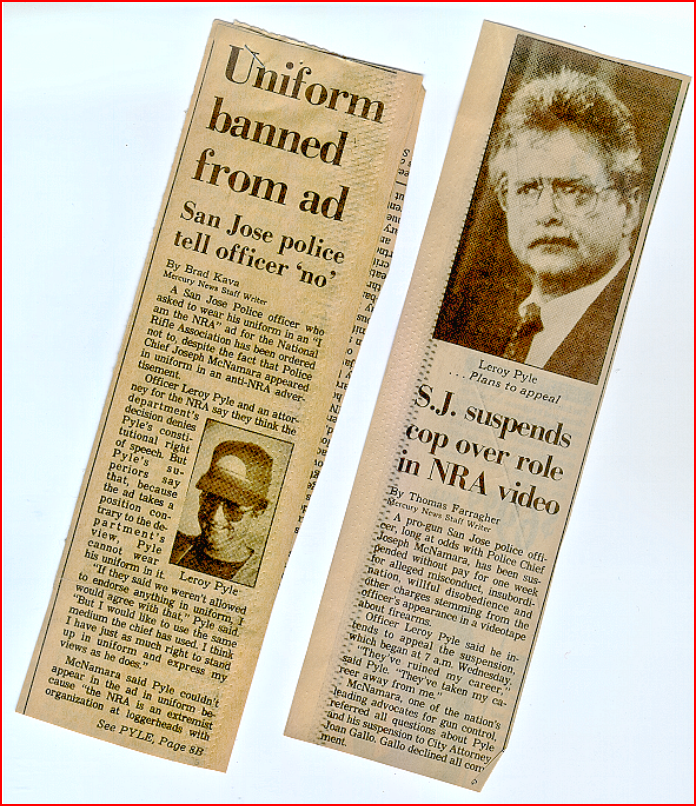

L.Pyle#2621

L.Pyle#2621

Joes gone. We are still here.

😄

Good video Leroy. You did a great job.

Thanx, Phil!

L

Hi Phil Pitts from Bill Clark in Montana, the one that left.

Good to hear you’re doing well Bill

Shortly after this the chief ordered me to appear on 60 Minutes, in uniform. He told 60 Minutes a semi-auto could be fired as rapidly as a full auto and would demonstrate. I told him it couldn’t happen. He told me he had already promised and I had better make it happen. In front of a couple of million people it didn’t happen!

Oh well…..

Amazing! I was not aware of that.

JoeMac was definitely a New Yawk liberal!😁 Hard to imagine just how unaware/unfamiliar he was with firearms!

L

Leroy great video still useful today. Technology changes but idiots never do.